Bombardment Of Charleston 1863-65

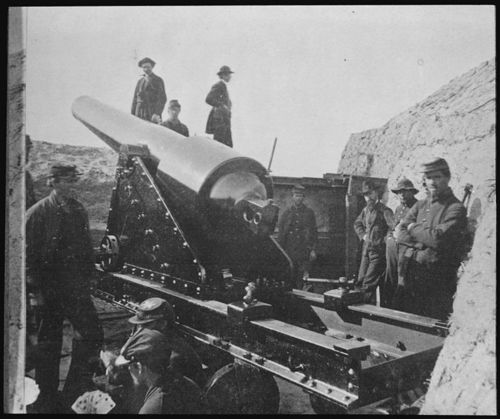

After the occupation of Ft. Sumter in Charleston harbor by Confederate troops in early 1861, the U.S. was focused on regaining control of our harbor in a slow, methodical campaign which would last until the end of the war. After an attack by Union ironclad ships in 1863 failed to gain control of Ft. Sumter, General Quincy Gillmore set in action a plan to reduce Charleston with artillery fire into the city. The first of the shelling began in August 1863 from near Morris Island with the Swamp Angel, an 8 inch Parrott rifled cannon which could fire 200 pound incendiary shells (authorized by Lincoln himself) 4-5 miles into Charleston, ranging as far north as Calhoun St. (some a little further). After the Swamp Angel was disabled on its 36th round, the shelling was halted (with the exception of 3 rounds fired in October) for a few months.

Then in November of the same year, the shelling was renewed with intensity, forcing the majority of the population of the city to move north of Calhoun St. to get out of range. This turned out to be fortuitous in that it reduced casualties among the civilian population. With this bombardment General Gillmore hoped to cause panic in the city and force the Confederate military to evacuate Charleston. This did not happen. Although this act of “inexcusable barbarity” (according to Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard) did cause some panic among the civilian population initially, over time it merely stiffened the resolve of the Rebels and civilians and for 545 days Charleston was on the receiving end of the longest bombardment in military history until the German siege of Leningrad in World War II.

According to Toomer Porter of Charleston, there were about 80 deaths as a result of the bombardment. Also the bombardment gave the North an opportunity to “experiment” with new technological advances in artillery with both guns and shells. Due to this, many of the projectiles hurled into Charleston never exploded….they were “duds.” Today, occasionally unexploded shells are found around the city and although they may have not exploded during the War Between the States, the black powder in the shells is still flammable, and the smallest spark could still ignite the powder, causing an explosion, injuring or killing someone 150 years later!

According to Toomer Porter of Charleston, there were about 80 deaths as a result of the bombardment. Also the bombardment gave the North an opportunity to “experiment” with new technological advances in artillery with both guns and shells. Due to this, many of the projectiles hurled into Charleston never exploded….they were “duds.” Today, occasionally unexploded shells are found around the city and although they may have not exploded during the War Between the States, the black powder in the shells is still flammable, and the smallest spark could still ignite the powder, causing an explosion, injuring or killing someone 150 years later!

The Union bombardment began right after the decisive Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg and so received relatively little attention in other parts of the country. I’ve discovered that many visitors to Charleston are completely unaware that at this time 150 years ago we were under bombardment and that they are within range of those shells anywhere south of Calhoun Street. The primary targets were the steeples of St. Michael’s and St. Philip’s Churches which were used by Confederate troops as signal stations. This caused the novelist, William Gilmore Simms to write:

“Aye, strike with sacrilegious aim

The temple of the living God.

Hurl iron bolt and seething flame,

Upon aisles which holiest feet have trod….”

The Bombardment of Charleston would continue unabated until Confederate troops evacuated the city in February 1865 and Federal troops moved in and occupied the city.

Charleston would be under Federal occupation for 12 years.

Note: This post is based on Johns Island, SC resident Chris Phelps’ book, The Bombardment of Charleston: 1863-1865 published by Pelican Publishing Company. Mr. Phelps is also the author of Charlestonians in War: The Charleston Battalion, published by Pelican.