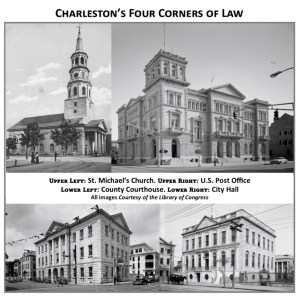

Charleston City Hall & the Four Corners of Law

By Mark R. Jones

Centrally located at the famous Four Corners of Law, Charleston City Hall is where the “Historic Downtown Tour” begins each day at 10 a.m. and 2 p. m.

City Hall, 1870s & 1950s Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The “four corners” nickname is attributed to Robert Ripley, who in his popular newspaper column, Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, claimed that the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets was the only place in the world which featured “four different laws.” St. Michael’s Church (1761) is “God’s law.” The United States Post Office and Judicial Center (1896) is “Federal law.” Charleston County Courthouse (1796) represents “State law” and City Hall represents “Municipal law.” It’s the only place in the world where this happens, believe it … or not.

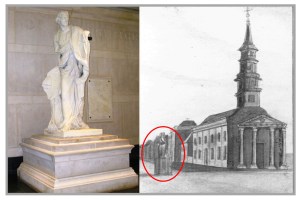

In 1770, a marble statue of William Pitt, member of Parliament who supported the colonists’ protest of the Stamp Act, was erected in the intersection. It was the first statue in America to commemorate a public figure. On April 17, 1780, during the British bombardment, a cannonball hit the statue and sheared off the extended left arm. The statue is currently standing in the lobby of the Charleston County Courthouse, about one thousand feet from its original location.

William Pitt statue, two views

Originally laid out to be a “Civic Square” in 1680, the Four Corners was set at an intersection “60 foot wide” on “two acres of land.” The City Hall location was the original beef market in colonial days. In 1796, the property was conveyed to the Federal government “for the purpose of erecting an Elegant Building thereon for a Banking House.”

Gabriel Manigault, the “gentleman architect,” is credited with the Adamesque design of the building with columns aligned in classic order – Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The Italian marble trim was purchased, ready cut, from Philadelphia. When the Bank of the United States was closed by Congress, the building served as the South Carolina State Bank between 1811-1818. When that bank failed, the property was conveyed back to the city, and has served as City Hall since that time. The Charleston City Seal appears in a low relief sculpture over the front pediment and, in Latin, reads: “The Body Politic, She Guards Her Buildings, Customs and Laws.”

In 1824, Lafayette was welcomed by authorities in City Hall, and in 1937, Eleanor Roosevelt was greeted with a reception. Due its central location, City Hall has historically been the meeting spot for hundreds of events and protests, good and bad. In July 1849, a white mob gathered on the steps in preparation of marching across the city to burn and destroy Calvary Church, an independent black congregation. Wild, and unsubstantiated, gossip had convinced many that the church was guilty of helping and harboring recent escapees from the Workhouse, the Negro jail.

As the mob assembled, James L. Petrigru, member of St. Michael’s Church across the street, and prominent lawyer, stood on City Hall steps and harangued the mob: “How can you be such damned fools, as to attempt to destroy this church, even if you have to set fire to the town? Have you not seen enough of fire here to be afraid of it? It is the only thing that decent men are afraid of!” His efforts saved the church from destruction.

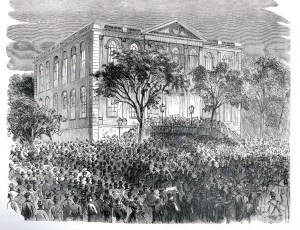

One of the most notable events was the massive crowd that gathered outside City Hall on November 6, 1860, awaiting the results of the Presidential election. A large board had been set up on the sidewalk on the and the state-by-state election tallies were updated as they were received from the Associated Press in New York via telegraph. By midnight, there were more than 4,000 people clogging Broad Street from East Bay to Meeting. The park behind City Hall was “shoulder to shoulder” with citizens. The police patrolled to keep prostitutes, pickpockets, and blacks from mingling with the crowd.

At 2:00 a.m. the news that Lincoln had defeated Douglas in New York arrived, which sealed the election. Dozens of men ran through the streets of Charleston until dawn shouting, announcing the news to those who had gone to bed. Voter turnout was 81.2 %, the highest in American history at the time. Lincoln did not carry a single slave-holding state and won the Electoral College with less than 40% of the vote. Six weeks later South Carolina seceded from the Union.

Thousands gather on Broad Street in front of Charleston City Hall, awaiting the results of the 1860 presidential election. From Harper’s Weekly. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One of the most notorious events happened in City Hall Council Chambers in October 1869 – Alderman T.J. Mackey and his nephew, Charleston sheriff and fellow alderman Edmund Mackey, exchanged gunfire. The issue that sparked the shooting was whether the City was responsible for paying the legal bill submitted David Corbin, a New York lawyer, for his lobbying to elect several members of the council. After a heated exchange in the council, T.J. Mackey stormed and a few minutes later re-entered as he “trembled with rage” and had “the appearance of an insane man … looked wild and his eyeballs were enlarged as big as his fists.”

Wearing his customary pistol belt, Mackey hollered at his nephew, “I shall have to chastise this fellow for his insolence” and drew his Colt Navy pistol. The two men wrestled in the council chamber until T.J. pointed his pistol at Edmund and pulled the trigger … the gun misfired. Edmund drew his own gun and fired “two wild shots in rapid succession,” and a moment later fired a third wild shot. The two men were apprehended, with T.J. dragged out of the chambers. He returned a few minutes later and said: “Mr. Mayor and gentleman, I have come into this chamber for the purpose of expressing my deep regret and shame.” He then claimed he was prepared to “show certificates from two doctors that while suffering very much to-day from my tooth, I took three grains of morphine, and I have not been myself since taking them.”

He was never arrested or charged. City Council tried him for “misconduct in office” and he resigned his seat and continued his career as a local judge.

After the 1886 earthquake the building went through extensive restorations and is the second-oldest city hall in continuous use in the United States. The Victorian council chamber is filled with an important collection of portraits and other paintings, the largest of which John Trumbull’s 1791 portrait of George Washington. Other works include portraits of Lafayette, Presidents James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson.

Mark Jones is a 20-year veteran Charleston tour guide, and the author of eight books about Charleston history and culture. He also posts a daily “Today In Charleston History” feature on his social media accounts. To learn more you can go to his website MarkJonesBooks.com