Robert Smalls: An Extraordinary Life

by Mark R. Jones

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in 1839 in Beaufort, S.C, in the home of Henry McKee, a cotton planter. The surname “Smalls” was most likely chosen by Robert after his emancipation. His mother, Lydia, was a house slave for the McKee family. In comparison to other circumstances, the McKees were such benevolent owners, Lydia worried that Robert would reach manhood without understanding the horrors of the institution into which he was born. To educate him, Lydia arranged for him to be sent to the fields to work and watch the slaves at “the whipping post.” He also had the advantage of living in the white household, wearing hand-me-down finer clothes of the McKee children, and learning more proper elocution so that he could speak without the traditional “Gullah” accent.

In 1851, at age twelve, Robert was sent to Charleston to live in the household of McKee’s sister-in-law, where he was “hired out’ by the family. McKee realized that the “hired out” Robert would net McKee more income from than he could get from the boy living in his Beaufort house. Hiring out was common in Charleston, where white owners hired out their slaves to provide services for the city, or for other businesses on a temporary basis. Robert worked as a waiter at the upscale Planter’s Hotel, and as a Charleston lamplighter. Mr. McKee allowed Robert to keep one dollar of his weekly wages.

When he was seventeen years old, Robert married Hannah Jones, a maid for a Charleston banker, Samuel Kingman. Although slaves could not legally marry, Mr. Kingman granted permission with the stipulation that the couple pay him $5 a month. Kingman also understood that married slaves were less inclined to run away.

By age 19, Robert was working fulltime on the Charleston docks as a stevedore for a white man named James Simmons, loading, and unloading the hundreds of ships that arrived in the harbor annually. It was Simmons who trained Robert to become a sailor and to pilot a small local schooner.

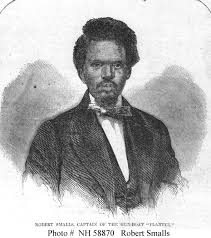

Robert Smalls. “Harper’s Weekly” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

After the birth of a daughter, and fearful that his family could easily be separated, like he had been separated from his mother at age twelve, Robert boldly asked Mr. Kingman to allow him to purchase his wife and daughter. They settled on the price of $800, which for Smalls was an impossible sum. Even if he managed to save the purchase price, he, himself, would remain enslaved.

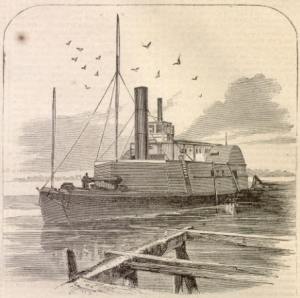

With the birth of his son in February 1861, and the outbreak of the War two months later at Ft. Sumter, Robert found new employment. He joined the crew of a steamer, the Planter, as a deckhand. Very quickly, the three white crew members noted Robert’s boating skills and he was soon promoted to wheelman.

The Planter was leased out to the Confederacy and was kept busy day and night transporting soldiers and military supplies up and down the Carolina coast. Robert stood at the wheel, next to the white captain, Charles Relyea, who wore a wide-brimmed straw hat only when he was on the water and left the hat in the pilot’s house when he disembarked.

Soon Robert viewed the Union blockade of Charleston harbor as a tantalizing promise of freedom. U.S. Navy ships were patrolling off the Charleston coast and under orders of the government, Navy commanders were accepting slave runaways as “contraband,” insuring their freedom. Smalls knew he would never be able to afford his family’s freedom but realized he could win their freedom by sea. He and Hannah agreed to act. As Hannah told him, “It is a risk, dear, but you and I, and our little ones must be free. I will go, for where you die, I will die.”

At 2:00 a.m. May 13, 1862, Robert, and a trusted number of fellow slave crewmembers, slipped the Planter from its berth at Charleston’s Southern Wharf, the headquarters for the commander of the Second Military District of South Carolina. As if their flight to freedom was not daring enough, Robert was stealing a Confederate vessel beneath the nose of the general’s headquarters! To escape, Robert knew he must be able to create the illusion that the Planter was just out on another routine delivery. So, he donned Capt. Relya’s wide-brimmed straw hat, and hoped that the pre-dawn gloom would disguise the fact that there were no white crew members aboard the steamer.

The “Planter” “Harper’s Weekly” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Instead of heading straight out of the harbor, Robert and the Planter sailed north up the Cooper River to where Hannah and the children were hiding on another steamer, the Etiwan, at the North Atlantic Wharf. The Planter’s movement upriver, and then backtracking could easily alert the attention of dozens of Confederate sentries posted along the harbor docks. Hannah and the children boarded the Planter, along with four other women.

As they sailed out of the harbor passing Ft. Sumter at about 4:15 a.m., Robert pulled the ship’s whistle cord – “two long blows and a short one” – the Confederate signal required to pass. Once the Planter was out of range of Ft. Sumter’s guns, Robert raised a white bedsheet and surrendered themselves to the three-masted clipper ship, Onward.

In less than four hours, Robert had accomplished an amazing feat: commandeering a Confederate ship from the commander’s dock and delivering its seventeen black passengers from slavery to freedom. Harper’s Weekly described it as “One of the most heroic and daring adventures since the war commenced was undertaken and successfully completed by a party of Negroes in Charleston.”

U.S. Congress passed a bill authorizing the Navy to award Robert and his crew the proceeds of the value of the Planter for “rescuing her from the enemies of the Government.” Robert received $1,500 which he used to purchase McKee’s Beaufort home off the tax rolls after the war.

In October returned to the Planter as part of the South Atlantic Blockade Squadron. In December 1863, he was promoted to captain and earned $150 a month. When the American flag was raised on Ft. Sumter on April 15, 1865, marking the end of the War, Smalls was on board the Planter for the ceremony.

After the War, Smalls served in the South Carolina Assembly and Senate, and served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He died in Beaufort on February 23, 1915, in the same house in which he had been raised as a slave, which he now owned.

“My race needs no special defense for the past history of them, and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” – Robert Smalls

You can learn more about Robert Smalls and the history of slavery in Charleston on our Charleston History Tour.

To learn more about Mark R. Jones and his books … CLICK HERE.