Some Charleston Romances

By Mark R. Jones

Anyone who has strolled Charleston’s quaint streets and hidden alleys has felt the faint echo of a more serene era, removed from the bustle of today’s America. For anyone interested in nineteenth-century Charleston culture Jane Austen’s novels (Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma) are accurate guideposts. With Valentine’s Day as the centerpiece of February, an exploration of a few of Charleston’s romances seems appropriate.

As Miss Austen so perfectly illustrated, many Charleston marriages of that day were based on monetary or political needs of the families involved. Few of the aristocratic children were able to marry for love. Rebel Sinclair wrote in her book Charleston At A Glance, “Slavery was not just rampant on the plantations where the high class made its wealth – the planters were also enslaved, to the expectations of society. Children of high society families often had to forsake personal happiness to ‘make a good match.’” Yet, despite those constraints, romance often found a way, one by lightning strike.

In 1777 the frigate Randolph spent two months being refitted at the Hobcaw shipyard in Charlestown. The ship’s mast had been struck by a lightning bolt in the harbor forcing several weeks of repair. Capt. Nicholas Biddle, who should have been at sea, attended a dinner party where he met Elizabeth Baker of Archdale Hall and began to court her. They became engaged within four months. So, thanks to a fortuitous lightning bolt, romance blossomed.

Martha Laurens was the favored daughter of American patriot leader, Henry Laurens. In 1779, Mr. Laurens was later captured by the British, accused of treason and was the first American imprisoned in the Tower of London. Upon his release on January 1, 1782, twenty-three-year-old Martha was in Paris, France to nurse her father back to health. During his convalescence Mr. Laurens was part of the American delegation negotiating the Treaty of Paris to end the American Revolution. Martha served as the official record-keeper of the treaty discussions for the American government.

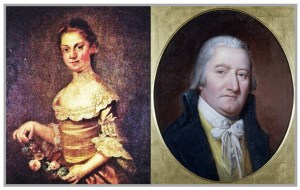

Martha Laurens and David Ramsay

When Martha and Mr. Laurens returned to Charleston, she met Dr. David Ramsay, who was assisting her father’s recovery. During his weekly visits to the family home Dr. Ramsay and Martha fell in love. She referred to her marriage as “a joint pilgrimage here on earth.” Martha died in 1811 and four years later, Dr. Ramsay was fatally shot on the street by an insane patient. As he lay in bed dying, surrounded by his children, he told them their mother was sitting on the bed next to him. “I have talked with her, and she urges me to forgive the man due to his illness … and if that is the price I pay to rejoin her, I gladly pay it.”

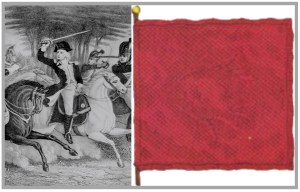

In 1779, calvary officer Col. William Washington arrived in Charlestown from Virginia. A cousin of Gen. George Washington, William participated in a skirmish against the British in Sandy Hill, the plantation of the Elliott family. Several nights later, William was invited to dinner at the Elliott plantation, and it became obvious to all that seventeen-year-old Jane Elliott was quite smitten with the dashing Virginia officer. She told him, “I will look for news of your flag and fortune.” Washington informed her that he did not have a standard. After dinner Jane cut an eighteen-inch square of crimson damask from her drapery and stayed up all night sewing the sleeve into a standard. The next morning, as the calvary unit was leaving she presented it to Washington, “Take this and make it your standard!” Washington attached it to a hickory pole and carried it until the end of the war.

The flag picked up the nickname “the Terror of Tarleton,” in reference to Washington’s British counterpart nemesis, Banastre Tarleton. It is more accurately called the “Eutaw Flag” since it was flag under which Washington was captured at the Battle of Eutaw Springs in September 1781. He was kept under house arrest in Charleston and during his confinement Washington proposed to Jane. They were married on April 21, 1782. After the war, the couple spent the next thirty years between the Sandy Hill plantation and their elegant Charleston townhouse at 8 South Battery. In 1827 Jane Elliott Washington turned over the Eutaw Flag to the Washington Light Infantry. The flag to this day remains in the infantry’s archives in Charleston.

Left: William Washington at the Battle of Cowpens. Right: The “Eutaw Flag” created by his future wife, Jane Elliott.

In the 1940s a scandalous romance occurred within the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement. Federal Judge Waties Waring, a scion of an old Charleston blueblood family, met Elizabeth Hoffman from Chicago. Elizabeth was very much a modern woman, opinionated and intelligent, a sharp contrast to the judge’s wife, the traditional subservient southern Annie Waring. Elizabeth was good gossip fodder among Charleston women as she made public pronouncements on race relations and political issues, a practice that locals believed were “unbecoming of a lady.”

The two quickly became romantically involved and in the fall of 1944 the Judge told his wife he wanted a divorce, while Elizabeth divorced her husband. Less than a week after the divorces were final, the Judge married Elizabeth, fifteen years his junior. The divorces and subsequent quick marriage rocked Charleston, as did Elizabeth when she became an even more outspoken civil rights supporter. The Warings were almost universally shunned by Charleston society. When the newly married couple would enter a room at social function, the room quickly emptied. Elizabeth was snubbed in local shops not only by other women, but also by the clerks.

On July 12, 1947, Judge Waties Waring ruled in favor of Elmore, an African American plaintiff in the case Elmore vs. Rice. Elmore had not been permitted to vote in the Democrat primary, so he sued for the right. In his decision Waring stated: “It is time for South Carolina to rejoin the Union … and adopt the American way of conducting elections.” Blacks were jubilant, but many whites were angry. The decision rocked the Jim Crow Era South.

As more civil rights rulings came favoring African Americans, the Warings were not only shunned, but also assaulted. Their renovated carriage house at 51 Meeting was attacked with bricks thrown through their windows, and the KKK burned a cross on the sidewalk. Judge Waring was publicly labeled as “emasculated, ”a condition forced upon him by his “Yankee wife.” On May 17, 1954, when the U. S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional, Judge Waring’s decision was cited as a landmark on the path leading to this decision. White Carolinians were shocked, angered, in disbelief. Many Charlestonians claimed that because the judge and his new wife had been shunned by society, he took his vengeance out by ruling against the white elite in civil rights cases.

The Warings ultimately moved to New York City, leaving Charleston behind. In October 2015, the Federal courthouse at 83 Meeting Street in Charleston was named the J. Waties Waring Judicial Center, half a block from the house where the judge lived with his “Yankee” wife.

J. Waties Waring Judicial Center at 83 Meeting Street. Photo by Sallie Dixon