The Old Exchange Building

By Mark R. Jones

For guests of the Charleston’s Alleys and Hidden Passages Tour, your meeting location – at the “Slave Auction” marker on the north side of the Old Exchange Building – is one of the most historic sites in the United States. To support Charleston’s burgeoning transatlantic trade, in 1767 the South Carolina Assembly allocated money for an “Exchange and Custom House, and New Watch House” on the site of the Half Moon Battery at the foot of Broad Street overlooking the harbor.

The Half Moon Battery was the original harbor fortification and Watch House built in the 1690s until it was razed for the construction of the Exchange. Part of the battery is now partially visible within the dungeon of the building. The Watch House was quite simply, Charleston’s first police station.

The Crisp Map of Charles Town & the Half Moon Battery

Completed in 1771, the Exchange Building has been the site of some of the most important events in South Carolina, and American, history. Initially it was property of the British, then the United States, then the Confederacy, then the city of Charleston, and currently owned by the South Carolina Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Over the last 250 years the building has been a commercial exchange, custom house, post office, city hall, military headquarters and currently, a museum.

Exchange Building, Harper’s weekly, 1850s

In 1773, Josiah Quincy visiting from Boston, described the new Exchange, “which fronted the place of my landing … a very handsome appearance.” Later that same year, with the passage of the Tea Act, American colonists began to protest the East India Company’s trade monopoly. When 257 chests of tea arrived in Charlestown it set off a crisis. At a mass meeting in the Great Hall of the Exchange, local merchants demanded the tea be sent back to England. Many in attendance threatened to burn the ship that contained the tea. The next day, in the pre-dawn hours, custom officials quietly off loaded the tea and stored it in the basement of the Exchange. When more tea arrived and was stored a “mob of several hundred men” chased Capt. Maitland from his ship, which was moved from the wharf in fear of it being burned. Three years later, in 1776, the Assembly sold the stored tea and used the money to support the Patriot troops in the area. Confiscated British gunpower was also stored in the Exchange basement, hidden behind a false bricked-in wall, which was never discovered by the British when they occupied the city in 1780-82.

Provost Dungeon

Charleston’s representatives to the First Continental Congress – Henry Middleton, John and Edward Rutledge, Thomas Lynch and Christopher Gadsden – were elected in the Great Hall. During the American Revolution, after Charleston fell to the British in 1780, the Exchange basement was converted into a military prison, known as the Provost Dungeon. More than sixty-one citizens were confined, including three signers of the Declaration of Independence – Edward Rutledge, Arthur Middleton and Thomas Heyward, Jr.

One of the most tragic prisoners was Col. Issac Hayne, who was publicly executed as a traitor in August of 1780. At 5:00 p.m. Hayne “was escorted by a party of soldiers to a gallows, erected within the lines of the town with his hands tied behind, and there hung up till he was dead.” The British purposefully marched Hayne past the house where his young children were living with his sister. During the march “the streets were crowded with thousands of anxious spectators.” Someone in the crowd called to Hayne “Exhibit the example of how an American can die!” Hayne replied, “I will endeavor to do so, sir!”

Issac Hayne

In May 1788, the South Carolina legislature met in the Great Hall and ratified the U.S. Constitution by a vote of 149-73, the eighth state to do so. Three years later, Pres. George Washington arrived in Charleston for a seven-day visit. He was greeted by the mayor at the Exchange Building where he stood on the balcony facing East Bay Street and watched a “procession in his honor to whom he politely and gracefully bowed as they passed in review before him.”

One his second night, Washington attended “an elegant dancing Assembly at the Exchange – At which were 256 elegantly dressed & handsome ladies.” According to newspaper reports the ladies were “all superbly dressed and most of them wore ribbons with different inscriptions.” Two nights later, Washington was once again entertained at the Exchange at a dinner hosted by Gov. Pinckney. Washington wrote in his diary “there were at least 400 ladies – the Number & appearance of which exceeded anything of the kind I had ever seen.”

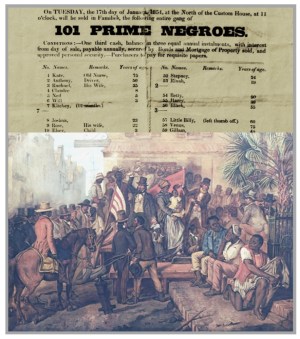

Charleston was one of the largest slave trading cities in the United States. In the 1800s, the area around the Old Exchange Building was one of the most common sites of downtown slave auctions. Along with real estate and other personal property, thousands of enslaved people were sold here as early as the 1770s. Most auctions occurred just north of the Exchange, though some also took place inside. Merchants also sold slaves at nearby stores on Broad, Chalmers, State, and East Bay streets. Enslaved Africans were usually sold at wharves along the city harbor. Some Africans were sold near the Exchange, but most people sold here were born in the U.S., making this a key site in the domestic slave trade. In 1856, the city banned auctions of slaves and other goods from the Exchange.

Slave auctions on the “north side of the Exchange”.

In 1912 the Exchange became the property of the Rebecca Motte Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, who were responsible for the extensive restoration of the building in preparation of the 1976 Bicentennial Celebration. Currently, the city of Charleston operates the Exchange as a museum for the DAR. We highly recommend everyone take a tour of this historic building.

Mark Jones is a 20-year veteran Charleston tour guide, and the author of eight books about Charleston history and culture. He also posts a daily “Today In Charleston History” feature on his social media accounts. To learn more you can go to his website MarkJonesBooks.com