The Path To The Civil War

By Mark Jones MarkJonesBooks.com

One of the seminal events of American history was the Confederate firing on the U.S. Army at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, on April 12, 1861. But long before that first shot landed, a thirty-year long bitter undercurrent of turbulence undermined the years in post-Revolutionary America. Starting with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, existing rifts between the Northern merchants and Southern planters grew larger, and more volatile. The Compromise was Congress’s weak attempt to stabilize the amount of free vs. slave states that joined the Union and managed to guarantee that the moral argument of slavery would remain a major issue.

In 1828 Congress passed the “Tariff of Abominations,” a crushing tariff in which Northern manufacturers got almost all the benefits of protection, while Southern farmers were forced to pay higher prices for comparatively inferior American products and lost their cotton export markets because of foreign retaliation against the United States. In 1832 Congress upped the tariffs still higher and South Carolina declared the new tariff unconstitutional, null-and-void. The state then began to purchase cannons and other arms and signing up volunteers to defend its state’s rights. Congress backed down and lowered the tariffs, but the clash bitterly alienated the North and South and the path toward secession became a thirty-year slippery slope.

During the last week of April 1860, the Democrat Presidential Convention was held in Charleston to decide who would run against the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln. The primary issue of the convention was, of course, slavery, and state’s rights. Most Northern delegates were either abolitionists, or at best, apathetic about the issues, while the Southern delegates were passionately, and unanimously, pro-slavery, and ardent defenders of the state’s rights doctrine.

Hibernian Hall, 1860, during the Democrat Convention. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In his opening speech South Carolina Congressman Lawrence Keitt claimed, “African slavery is the cornerstone of the industrial, social, and political fabric of the South. We contend that slavery is right, and that this is a confederate Republic of sovereign states.” Southern delegates then proposed a platform plank stating that “Congress has no power to abolish slavery.” It was defeated 165-138, and fifty-one of the Southern delegates walked out of the convention. The remaining delegates were unable to agree on a nominee and after fifty-seven ballots, the Convention adjourned with no presidential nominee.

Six weeks later, the Northern Democrats met in Baltimore and nominated Stephen Douglas, while the Southern Democrats met in Richmond and nominated the sitting vice president, John Breckinridge from Kentucky. Adding to the confusion, there was a fourth presidential candidate, John Bell of the Constitution Union Party. On November 6, 1860, Lincoln was elected with 40% of the vote, and the next morning the Charleston Mercury exclaimed, “The tea has been thrown overboard – the Revolution of 1860 has been initiated.”

South Carolina Institute Hall, during secession. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

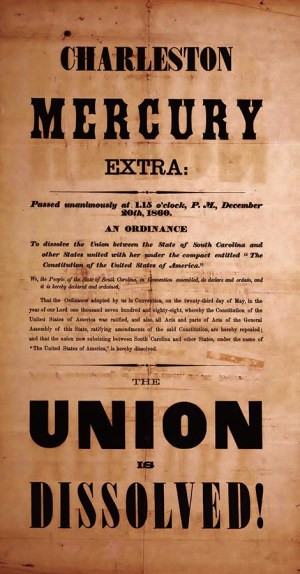

On December 20, the South Carolina legislature, meeting in Charleston due to a smallpox outbreak in the capital city of Columbia, voted 169-0 and form the Republic of South Carolina. The Mercury published an immediate “Extra” edition, a single broadsheet that screamed: THE UNION IS DISSOLVED!”

Broadsheet from Charleston Mercury. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Three months later, Gen. Pierre Gustav Toutant Beauregard arrived in Charleston as the first brigadier general of the Confederate Army and assumed command of “all forces in and about Charleston Harbor.” He immediately stopped the weekly supply deliveries to Fort Sumter and within a month, forty-three cannons had been mounted by the Confederacy at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, and Fort Johnson on James Island, essentially putting the U.S. Army at Sumter in a dangerous crossfire.

On April 10, Confederate president, Jefferson Davis issued an order to Beauregard to take Fort Sumter: “You will demand its evacuation and, if this is refused, proceed in such manner as you may determine to reduce it.”

The next day Beauregard sent a letter to Major Robert Anderson demanding the surrender of the fort. Anderson had been Beauregard’s artillery instructor at West Point, and Beauregard had subsequently replaced Anderson in that position. Anderson wrote his refusal and then told Col. James Chesnut, former U.S. Senator, and Beauregard’s most senior aid, “Gentlemen, if you do not batter the fort to pieces about us, we shall be starved out in a few days.”

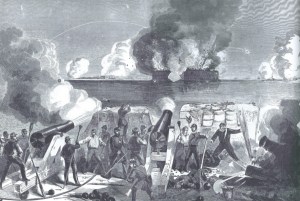

About 3:30 a.m. on the morning of April 12, Col. Chesnut returned to Fort Sumter with the following note: “Sir: By the authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard … we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.” One hour later, 4:30 a.m., a mortar shell from James Island exploded above Fort Sumter like a fireworks display and within a few minutes, the forty-three Confederate guns were all firing at Sumter in a practiced rhythm.

First shot fired from Ft. Johnson, by Capt. George James. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In Charleston, the bombardment became a spectacle. As dawn broke, the streets were filled with people rushing to find a vantage point to watch the battle. The Battery seawall was quickly crammed with ladies and gentlemen in their finest attire. Anna Brackett wrote, “Women of all ages and ranks of life look eagerly with spyglasses and opera glasses.” During the first day, more than 2,500 shots were fired.

Charleston citizens watching the bombardment from the Battery. From the Illustrated London News.

During the second day, the upper section of Sumter was on fire, and by early afternoon, the fire was spreading. Col. Louis Wigfall of Texas, one of Beauregard’s aids, sailed out to Sumter waving a white handkerchief and offered a truce. Anderson, who was down to his last three shots, with his soldiers half-starved and exhausted, agreed.

Church bells rang throughout the city and the spectators on the seawall cheered hysterically. The next day, at noon, April 14, the Federal garrison saluted the American flag with a one-hundred-gun salute. The harbor was filled with thousands of Charlestonians, in every kind of boat imaginable, to watch the surrender.

Private Daniel Hough was assigned to the 47th gun of the salute. Hough loaded the gun, preparing to fire, when a spark in the gun barrel set the cartridge off. The gun exploded, blowing off Hough’s right arm and instantly killing him, as well as detonating ammunition stored next to the gun. Although Hough was buried on the Fort Sumter parade ground during the surrender, it is not known where his remains are now. More 600,000 thousand were killed during the Civil War, but the first casualty was an American soldier saluting the flag.

Mark Jones is a 20-year Charleston tour guide and author. You can read the entire story of on the firing of Ft. Sumter in his book CHARLESTON FIRSTS.